The First Year, 1934-35

THE STORY OF ROUND TABLE, nationally and internationally was told by John Creasey in 1953 in Round Table, the First Twenty-five Years. In these pages is the shorter story of one of the member Tables of the movement, the National Association of Round Tables of Great Britain and Ireland. It is the story of the Round Table in Scarborough.

When in 1927, with an enthusiasm and a foresight that were to become characteristic of the movement as a whole, the first Round Table Club came into being at Norwich, the ripples extended slowly but surely throughout the country, reaching Scarborough in 1934. They had already encircled her, having earlier reached Middlesbrough, Hull, Bridlington and York in that order.

As Rotary Clubs had done and were still to do in many more cities and towns, the Rotary Club of Scarborough assumed the functions of an avuncular midwife, and the successful birth of the Scarborough Table can be attributed directly to its initial efforts. The Founder Chairman of the recently formed York Table, J. M. Gray, had been invited to speak at one of its luncheons. At that time the Rotary Club’s President was Mr. G. H. Fawcett, its Secretary was Mr. Andrew Sinclair, and among its membership were three who were distinguished by their youth, for none had reached the age of 40. They were Frank Winn, Norman King and Geoffrey Hazell.

Gray had made a good case in his presentation of the ideas and ideals underlying the Round Table movement, with which Rotary had been sympathetic in both theory and active ever since the formation of the Norwich Table. The President and Secretary of the Scarborough Rotary Club [1] called a meeting of eight under 40’s, including the club’s own trio, who were arbitrarily deemed to be potential Table members.

Such potential members had to fall within fairly well-defined categories. They had necessarily to be:

a Under the age of 40

b Of responsible executive status

c Of varied occupational classifications

d Of such character as would cause them to give of themselves for the good of their fellows.

This meeting was held at the Esplanade Cafe on Monday, 17th December 1934. Although doubts were expressed whether there would be sufficient suitable men in a town the size of Scarborough who would fulfil the broad requirements of membership, seven of the eight men present committed themselves to the formation of a Table.

Thus the seven Founder Members to emerge from that historic, informal and unminuted meeting were:

S. D. McCloy, Solicitor – Chairman

Frank Winn, Chartered Secretary – Vice-Chairman

T. S. Singer, Architect – Hon. Secretary

John C. Whitfield, Solicitor – Hon. Treasurer

Ralph K. Rowntree, Departmental Store – Council Member

Norman L. King, Dentist – do.

Geoffrey S. Hazell, Ladies’ Outfitter – do.

The first minuted meeting, held on 7th January 1935, in effect confirmed the decisions taken at the December meeting. Messrs. G. H. Fawcett and Andrew Sinclair were elected President and Vice-President respectively in graceful acknowledgment of the part Rotary had played in bringing the Table into being.

At this meeting it was resolved that Table meetings should be held fortnightly on Fridays at 1.10 p.m. and the names of 13 eligible under 40’s, among them hoteliers, motor engineeers, bankers, furnishers, police officers and estate agents, were suggested for personal approach with a view to membership.

Early Days

Much work inevitably fell on the Council – contact with the National Association of Round Tables, formulation of rules, [2] venues for meetings, speaker-finding and all forms of club activities. An overriding consideration was the quality of membership.

‘The attempt was made,’ said McCloy many years later, ‘to try to assess fully before election whether a particular candidate could contribute something to the Table. The principle was adopted that we should go slowly at the start to build a Table of members who were congenial and representative, rather on Rotary lines, of a fair cross-section of the community. We were always in the early days careful not to allow the Table to grow so fast that the new members could not be readily absorbed, thus enabling the fairly close ties of friendship to be built up.’

This is borne out by a minute of 26th March 1935, that not more than four new members be admitted per month, this being two at each meeting. One has but to look back over the years to realise the wisdom of this early policy, on which the subsequent strength of the Table was firmly based. What happened in Scarborough parallelled what happened in many other Tables throughout the country. Fellowship led to friendship and many friendships, first made in the Table, have continued throughout life.

The first luncheon meeting took place at the Esplanade Cafe (which was then the home of the Rotary Club) on Friday, 18th January 1935, eleven days after the inaugural meeting. The second and subsequent fortnightly luncheons were held in the Cricketers’ Room at the Grand Hotel from

1.10 to 2.25 p.m. at a cost of 2/9 ‘including a tip of 3d’.

The Council’s next step was to decide that an Attendance Register should be kept, and to set up three sub-Committees:

a Fraternity Committee: to take charge of all matters relating to hotel accommodation, menus, payment for meals, Table property and classification badges; to promote a fraternal spirit within the Table and to foster its social life by arrangement ing various activities such as dinners and dances; to arrange for the proper welcome of visitors and new members

b Speakers Committee: to prepare a syllabus of the Table programme and arrange speakers.

c Membership Committee: to deal with all matters pertaining to the invitation, election and conduct of members.

The First Table Job

In March came the Table’s first of many incursions into [3] social service. The Silver Jubilee of H.M. King George V was to be celebrated, and the Scout movement had evolved ambitious plans. Table representation on the Executive Committee of the Scarborough and District Scouts’ Association was invited.

Maurice Plows, on condition that he did not have to wear shorts, agreed to serve, and consideration was soon being given to the help that the Scouts would need in their arrangements.

Beacons were to be built round the whole of the coast of the country and lit at an appointed time. Scarborough was to be responsible for three – one on Castle Hill, another on the Racecourse and the third at Ravenscar. The Ravenscar beacon was the one on which the Table’s attention was concentrated.

‘It was quite a job, I well remember’, wrote Maurice Plows more than thirty years later. ‘We had, of course, to get fuel for the fire. I got two lorry loads of old tyres from Tesseymans delivered at the site near to the road leading down to the Hall.

‘We contacted the various people connected with the forests: I don’t think it was called the Forestry Commission then. Loads and loads of wood were taken to the site. This was to be our first big job in Community Service and naturally we wanted the best fire. As it was, the other two were poor affairs and soon burnt out.

‘I got a furniture van from Tonks via Howard Tonks Jackson, and into it we loaded all the scouts along with their tents, food, beds etc., and we set off for Ravenscar. There we directed the scouts to build the fire along with ourselves, about half a dozen members of the Table. We got the scouts to dig a deep pit in a circle round the fire and this we filled with water and kept full buckets ready for the actual fire.

‘On the big night the whole Table went to Ravenscar to get the fire going; I cannot remember if we had fireworks or not. I do remember that we all went to Raven Hall and had a dance, and then at midnight a lot of us went to the swimming pool.’

This was the first, not only of the Table’s Social Service activities, but of its efforts to help the Scout movement. [4]

‘During my office on the Scouts executive,’ recalls Maurice Plows, I found that quite a few of the scouts who were crippled or ill could not get to attend their Wednesday meeting sso we got out a list of those in R.T. and Rotary who possessed cars; not a lot of us did in those days.

‘A rota was drawn up for the scouts to be picked up and taken to their meetings. This worked very well indeed and continued until the war broke out when we lost members and petrol rationing etc. stopped activities.’

Conferences

This (1935) was the year of the Hastings Conference, at which S. D. McCloy, W. E. Hopwood and Frank Winn represented the Scarborough Table. The various proposals on the agenda were considered in some detail by the Council, and the Table’s delegates given careful instructions how to vote.

It was following this conference that the Scarborough Table, barely six months old, cheerfully agreed to invite the national body to Scarborough for its next conference but one, the 1936 venue being London. Somewhat to its surprise the Table found its invitation taken up by the National Council.

The dates were to be 27th to 29th May 1937.

The invitation was not, of course, officially given until the 1936 Conference. It was made by Frank Winn, supported at the meeting by R. K. Rowntree, H. I. Dennis, G. S. Hazell and H. D. Tesseyman, and it was accepted with alacrity and acclamation.

The curious thing about a conference is that a delegate will soon forget the business transacted but long remember quite irrelevant details. The London Conference was a case in point.

‘The Scarborough party,’ Frank Winn remembers, ‘stayed at the Cumberland Hotel. My room-mate was Bert (H. I.) Dennis. I got up one morning to find his bed was unoccupied. The window was wide open and there was a drop of about 120 feet outside. I could see nothing unusual below, but I dashed along to tell Dennis Tesseyman the news; we were both really hot under the collar. Bert turned up later, his bright and breezy self. He had got up very early and had gone to see a relative in one of the London suburbs.’ [5]

The contingent’s main recollections appear to centre round the Conference Banquet at the Connaught Rooms. The National President rose with hospitable frequency to take wine with the delegates from the various Tables. There were sufficient Tables for the Scarborough quintet, with characteristic irreverence, to spend the meal debating the time when, instead of rising above the table, he would sink beneath it.

The cabaret that followed is remembered by more than the Scarborough delegates, and it taught all potential Conference organisers a lesson. The star turn was a popular and highly paid Cockney raconteur whose choice of material would have been admirable for a seasoned all-male smoke room audience. In a young mixed audience in their twenties and thirties he produced a profound mass-embarrassment. Red-faced Conference stewards tried to shush him from the screen that did duty for the wings, then they appeared on the platform to plead with him, and in the end to whisk him off in the middle of a word. The following year Scarborough played safe.

An innovation in the first year of the Table was the Donations Box. It was the result of a resolution of the Council at a meeting on the 2nd August 1935* that ‘a box should be passed round at all future Table meetings and that members present should contribute such sums as they choose, not exceeding 3d, and that the proceeds should be devoted to such charitable objects as the Table shall from time to time decide’. It was not until some months later that the Secretary was empowered to leave the box at the hotel office instead of taking it home with him after each meeting.

[* This was the meeting at which Ralph Rowntree reported on the cost of the lamp-standard presented to Dennis Tesseyman on the occasion of his marriage, the minute book containing the classic resolution: ‘Resolved that the presentation committee should collect 2/3 from each member (Tesseyman excluded)’ ]

In October the luncheon venue changed to the Pavilion Hotel, still at 2/9. Certain other Tables in the Area considered this a rather high figure, no doubt indicative of plutocratic tendencies on the part of Scarborough’s membership. Hull, for instance, at that time was paying 1/9 at the old White House Hotel which, incidentally, was then a temperance hostelry. [6]

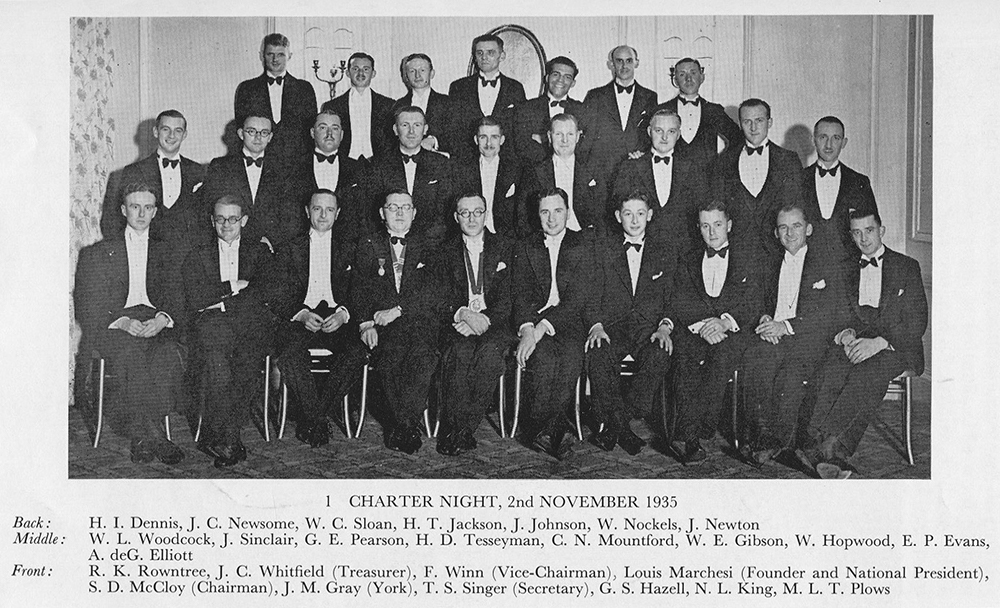

Charter Night

The last major activity of the Scarborough Table’s first year was the presentation of the Table’s Charter at a dinner held at the Pavilion Hotel on 2nd November 1935. Louis Marchesi, the founder of the movement and in that year National President, accepted the Table’s invitation to come up north to present it.

Distinguished guests included the Mayor, Councillor (later Alderman) F. C. Whittaker, J.P., whose son Meredith, twelve years and a world war later, was to become Table Chairman; the Town Clerk, Mr. Sidney Jones; the Member for Scarborough, Sir Paul Latham, M.P., and the assembled company included representatives from most of the Tables in Yorkshire.

During the summer, joint outings had been arranged with the York and Hull Tables which, with Bridlington and Scarborough, comprised No. 10 Area. After the summer, additional to the fortnightly luncheons, monthly evening meetings were arranged. Then surplus energy was worked off on a Club Walk which the Council resolved ‘should not be less than ten miles’. This appears to have been reasonably successful, for other walks followed.

Hitherto the activities of the Table had been exclusively male. Signs of limited acknowledgement of the existence of wives, fiancées and girlfriends, however, appeared at the end of the year when it was decided that they should be invited to the Christmas luncheon.*

[*It took, however, a further quarter of a century for a Council resolution to be passed in 1961 that the names of wives should be included in the Directory, with the minuted content that Tom Pindar disclosed a remarkable and suspicious knowledge of most of them.]

Speakers

From the beginning considerable attention was given to speakers and their subjects. The Speakers’ Committee had to bear in mind a Council directive that all aspects of the Round Table movement should receive proper representation and, in particular, that ample opportunity should be given for discussion of business matters concerning both R.T.B.I. and the Scarborough Table. This was all very well, but enough is as good as a feast. The Committee wisely widened its own terms of reference. [7]

Current topics were discussed and debated. Speakers were found who spoke authoritatively on Scarborough itself, on local government, on unemployment and other social problems of the day, and on matters of wide general interest. Quite early, for example, the Table debated two topics that today, after more than thirty years, are still remarkably up to date:

1 That the extensive practice of selling goods on the hire purchase is to be deplored.

2 Is the present tendency of exaggerated advertising effective?

The Table’s own membership threw up speakers on the various aspects of their own jobs. Such vocational talks not only had a continuing interest to the listener, but in some cases gave a novice his first audience, a sympathetic and friendly (but not necessarily uncritical) audience within the fellowship of the Table.

This was not peculiar to Scarborough. In Tables all over the country there was a membership varying in age between the early twenties and the late thirties, a hand-picked membership selected not for what it could get from, but for what it could give to the Table and the community. But in giving, it gained.

This duty, for it was and is a Table duty, of having to get up and say something, whether to make an announcement, to give a talk, to propose a vote of thanks, to give a toast or even to say Grace, is but one of many things that have helped a shy and diffident youngster to gain poise, to overcome butterflies and often to emerge with a quiet confidence into wider spheres.

Finally, what were members to call themselves? This problem had been in existence far longer than the Scarborough Table had. The practice had grown up in many Tables, and perpetuated in the magazine, News & Views, of referring to them as Tablers.

A letter from a member of the Hull Table to News & Views in which, amongst other things, this word was referred to as an incorrectly derived etymological abortion, sparked off a controversy that continued for some time. It eventually died, probably because even worse misuses of the English language were, in spite of A. P. Herbert, constantly burrowing their way into current usage. [8]

Hull dropped the word; it could not very well do anything else with a militant purist in its ranks. The word Member was used instead. So it was in the Scarborough Table, which had purists of its own, and within four months of its foundation a recommendation was being sent to the National Council that the use of the objectionable word be discouraged. As a matter of interest it does not appear in the Minute Book until 1948, and then but fleetingly. It creeps in again in 1954, occurring with increasing frequency in and after 1957. [9]

You must be logged in to post a comment.